Medical missions are trips in which trained medical professionals travel to foreign countries with a specific medical purpose for a designated period of time. The purpose of such trips are to provide free medical services to low income and underserved communities, and to also act as a beacon of light and hope for people who often feel abandoned and forgotten about.

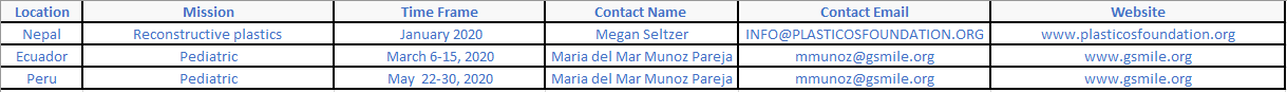

Upcoming Missions

Doctors Without Borders is urgently recruiting anesthesiologists for field projects – anesthesia providers often work in conflict settings to provide care to communities without access to functioning health care systems.

For more information, visit: http://bit.ly/MSFAnes.

To apply, send CV to: [email protected]

For more information, visit: http://bit.ly/MSFAnes.

To apply, send CV to: [email protected]

NYSSA Member Stories

‘Good Copy, Oscar Tango’: A Medical Mission in Nigeria

This article was printed in the NYSSA's Sphere Quarterly Publication - Volume 69 Number 2, Summer 2017

by KIRI MACKERSEY, M.D.

All photos courtesy of Kiri Mackersey, M.D.

“How about Nigeria?” The job was at a large, long-standing maternity hospital in northern Nigeria with Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), an independent, medical humanitarian organization. It was my first assignment. My role would be head of the obstetric ICU and supervisor of the local nurse anesthetists in the operating rooms. MSF’s emergency obstetrics program at the Ministry of Health hospital in Jahun, Jigawa State, Nigeria, provides obstetric care and offers surgery for women with vesicovaginal fistulas. Although other areas in the north had been devastated by the ongoing conflict between Boko Haram and the Nigerian military, the security situation in Jahun was stable. The expat compound was colloquially known as Jahun Paradise and was rumored to have the best cook in MSF. I signed up.

New York — Paris — Abuja — Jahun

I had been warned that Abuja Airport would be a goat-filled market of chaos and danger — don’t talk to anyone after the security gate and don’t walk out with anyone, even if they say that they are a policeman. In place of livestock, however, are businessmen, tourists, families coming home and a Nigerian movie star whose entourage rivals that of the Kardashians. I spend a couple of nights in Abuja receiving security and medical briefings before heading to Jahun.

The drive is about five to six hours to Jahun, depending on traffic.

The drive takes seven hours on a good day … without military roadblocks.

You’ll be driving for eight hours, depending on weather.

Are you ready for a nine to ten hour drive, more or less?

At this point, I stop asking how long the drive to Jahun will take.

ICU: India Charlie

We arrive in Jahun in the late afternoon. Finally I see the promised goats surrounded by a distinct lack of chaos or danger. My Australian predecessor wastes no time showing me around the hospital. I put down my bags and 10 minutes later I’m on an ICU round. The ICU has eight beds run by a local staff of two nurses and a charge nurse, Helene. At the start and conclusion of the round I am greeted with “The new med anesthetist! You are welcome.” At the door to the ICU we wash our hands and change from outside shoes into rubber clogs and white coats. The room is simple and functional, each bed separated by a nylon curtain. The head of the bed can be raised mechanically and every component can be wiped clean. There are several fans and two air conditioning units that provide welcome relief from the heat outside. We start the round immediately at bed one.

Bed one: an 18-year-old G3P0 with eclampsia. She was seizing at home for about nine hours before she was brought in and delivered a deceased term baby last night. BP 185/101. No hyperreflexia, no headache. Magnesium treatment is halfway complete and she’s on labetalol. The labetalol is increased. Bed two: a 20-year-old G4P1, eclampsia. Seized again last night despite magnesium. There’s a low-grade fever and she’s drowsy and incoherent. We start a discussion: is it a postictal state, a stroke in progress, magnesium or the benzodiazepines used to break the seizure? Blood pressure is controlled, pupils equal and reactive, limbs are symmetrically hypotonic. Continue magnesium, check mag levels and electrolytes, rapid malaria screen. In my head I imagine the work-up she would receive in New York: a CT head, cultures from every orifice, anesthesia team on standby to intubate. Bed three: 25-year-old G6P3, eclampsia. She has finished magnesium treatment and is on oral antihypertensives.

Northern Nigeria has one of the highest rates of preeclampsia in the world. No one knows exactly why. It could be nutritional deficiency in magnesium or a genetic predisposition, but more universal reasons, such as second marriages with multiple gestations, cannot be ruled out. The American obstetrician on our team shakes his head. He’s never seen three recently eclamptic women in the same room before. “Sahnu?” The patient in bed three nods. “Sahnu” is Hausa, the predominant language in this area. It is one of those indispensable, Swiss Army pocketknife words: how are you?/I’m fine/hello/thank you/OK/I’m sorry. By the end of my mission it forms the backbone of my vocabulary.

We move on. Bed four: a 17-year-old G1P1, jaundice, abdominal distension, renal failure, lethargy, normotensive, no seizures. Her baby is in a crib beside the bed. We stand around scratching our medical heads. One of the local doctors suggests herbal toxicity. The woman has been taking a local herbal concoction of potash and plants to speed labor — her tongue is still dark from the ash. These mixtures are usually made by traditional healers and come with a high risk of liver failure. Will the lab do liver enzymes? Our new French lab technician has recently catalogued the reagents — she is hopeful. The obstetric ultrasound confirms ascites. I move up onto her chest. The curvilinear ultrasound probe just about fits between her ribs and I see a hyperdynamic, empty heart. We start IV fluids and discuss transfer to a larger state hospital.

The women in beds five and six have recovered from postpartum bleeds and are ready to move to the step-down beds in the adjacent room. Helene calls their names out the window. The central courtyard is full of waiting aunts and grandmothers who feed, wash and transfer our patients. “Fatima … Family of Fatima! Come to the ICU.” A few minutes later, Family of Fatima is cloaking her in a long hijab and bright cloth “wrappa,” the traditional dress in this area. They scoop up her brightly bundled baby and walk across the doorway into the general ward. Here she will have her own bed for a couple of nights, then she will share her bed with another postpartum patient before returning to her own village. As they pass me, the women raise their hands and bow their heads: “Sahnu! Sahnu! Sahnu!”

Bed seven: a 16-year-old G1P1 with anemia. Her presenting hemoglobin was 2, presenting complaint: dizziness while walking. She had delivered at home two days previously and her baby is beside her. After 4 units, the hemoglobin on our bedside fingerstick is now 6. She feels good. We debate transfusing another unit. She is nutritionally deprived and is about to spend the next few months breastfeeding. I grab the obstetric ultrasound probe (my echo). Her left ventricle is hyperdynamic and relatively empty. We take a vote and the transfusers win. We also add some high-calorie nutritional supplements.

We turn to our last bed. She’s 35, G5P2 with weakness. She was brought in by her family an hour ago, unresponsive. The story is that she delivered at home overnight. She then became confused and lost consciousness in the early hours of the morning. It’s now evening. The outgoing medical anesthetist educates me: only the men drive and they may be reluctant to travel at night or in poor weather. Our admissions come in mainly between 9 a.m. and 11 a.m., regardless of the onset of symptoms. Some women travel for days, from neighboring countries, for the free, highquality care that MSF delivers. The lucky ones come by car, the rest by oxcart. Our patient flails her left side but her right side is immobile. Blood pressure is uncontrolled, Babinski’s ... I have not checked for this sign since I was a medical student. I doubt myself and repeat the test. Up-going. Her prognosis is grim. Long-term treatment facilities and rehab units do not exist in Jahun and her ongoing care will place an enormous burden on her extended family. The team is silent for a moment, deeply aware of the repercussions if no recovery is made.

The static of a walkie-talkie breaks my reverie. India Charlie, this is Oscar Tango, do you copy? We copy. India Charlie, is the med anesthetist with you? We need help in Oscar Tango. Good copy, she’s coming.

Operating Theatre: Oscar Tango

The nurse anesthetist is struggling with an intubation. I take over and, after the tube is in, find out what is going on. Uterine rupture from a combination of eclampsia and protracted labor. Extra IV lines are secured and we cover her with a washable forced air warmer. Fresh blood is ordered from the blood bank. It arrives four minutes later, still warm from donation. In Jahun, the family of the patient “repays” by donating the number of units used by the patient. There is always a line of willing husbands and fathers on the bench outside the blood bank, waiting for a spot in the “bleeding room.” The type and screen is done on a large porcelain tablet. Blood is screened for hepatitis, HIV, syphilis and malaria. Malaria positive blood is still used — in an endemic area, too many units would be wasted otherwise — but the recipient is simultaneously treated. Packed cells are available for the neonates, everyone else gets whole blood.

Hysterectomy underway, I explore the drug cabinet. It’s fully stocked with a familiar family of emergency medications. Stacks of single-use syringes and needles are neatly organized. A separate, locked shelf contains controlled substances and there is a log book in the office nearby for periodic inspections by the Ministry of Health (MOH). All controlled substance containers are discarded separately. The MOH inspector will compare the log book with the collection of vials. While I understand how narcotics and benzodiazepines made the controlled list, the reason for locking up ephedrine, caffeine and methylergometrine is more of a mystery.

I turn to the anesthesia machine. I had read the orientation pack but the chrome box is quite different in practice. The nurse smiles. “Not like the one you are used to?” It reminds me of a gramophone from 1950.

I follow a standard mental algorithm: first find the “on” switch. There are six dials and two pressure gauges on the Monnal D2. My predecessor points out the pressure dial, rate setting and pressure alarms. There’s an oxygen blender and an isoflurane vaporizer. Monnal has continued manufacture of these simple models as a service to medical NGOs — they are easy to maintain, easy to transport and difficult to break. In terms of the circuit, everything except the endotracheal tube is reusable. The sterilization room has a counter window into the operating theatre — central supply gives us immediate service!

The next five weeks of my assignment pass quickly. I’m on call around the clock and every few days there is a soft nighttime knock at my door. Sometimes I’m called to help with mystery diagnoses (a thyroid storm, an acute non-obstetric abdomen, liver failure, psychosis mimicking a stroke) or to the operating room when a spinal won’t go in easily for an overnight C-section. I use the OB ultrasound for echo often, and rapidly discover that these young women have far from young hearts. Admissions for heart failure come in two or three times a week and some have concomitant valvular disease. I dredge up knowledge from medical school, consult my pocket pharmacopeia, and ask the local doctors if this is what a malaria spleen feels like. Every day I feel humble and grateful.

How to treat burnout? Talk to colleagues, get a massage? Rest on holiday? Quit your job? Become an administrator? Perhaps. For anyone who still has the embers of medicine alight, my advice is to drop the pressures of the Joint Commission, escape the clipboards and walk away from the man who didn’t like the “feel of the pillow” in PACU. Go and treat people who ask for nothing and give only gratitude in return. I hope I helped them. There is no doubt that they helped me. ■

Kiri Mackersey, M.D., is an attending cardiothoracic anesthesiologist at Montefiore Medical Center.

This article was printed in the NYSSA's Sphere Quarterly Publication - Volume 69 Number 2, Summer 2017

All photos courtesy of Kiri Mackersey, M.D.

“How about Nigeria?” The job was at a large, long-standing maternity hospital in northern Nigeria with Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), an independent, medical humanitarian organization. It was my first assignment. My role would be head of the obstetric ICU and supervisor of the local nurse anesthetists in the operating rooms. MSF’s emergency obstetrics program at the Ministry of Health hospital in Jahun, Jigawa State, Nigeria, provides obstetric care and offers surgery for women with vesicovaginal fistulas. Although other areas in the north had been devastated by the ongoing conflict between Boko Haram and the Nigerian military, the security situation in Jahun was stable. The expat compound was colloquially known as Jahun Paradise and was rumored to have the best cook in MSF. I signed up.

New York — Paris — Abuja — Jahun

I had been warned that Abuja Airport would be a goat-filled market of chaos and danger — don’t talk to anyone after the security gate and don’t walk out with anyone, even if they say that they are a policeman. In place of livestock, however, are businessmen, tourists, families coming home and a Nigerian movie star whose entourage rivals that of the Kardashians. I spend a couple of nights in Abuja receiving security and medical briefings before heading to Jahun.

The drive is about five to six hours to Jahun, depending on traffic.

The drive takes seven hours on a good day … without military roadblocks.

You’ll be driving for eight hours, depending on weather.

Are you ready for a nine to ten hour drive, more or less?

At this point, I stop asking how long the drive to Jahun will take.

ICU: India Charlie

We arrive in Jahun in the late afternoon. Finally I see the promised goats surrounded by a distinct lack of chaos or danger. My Australian predecessor wastes no time showing me around the hospital. I put down my bags and 10 minutes later I’m on an ICU round. The ICU has eight beds run by a local staff of two nurses and a charge nurse, Helene. At the start and conclusion of the round I am greeted with “The new med anesthetist! You are welcome.” At the door to the ICU we wash our hands and change from outside shoes into rubber clogs and white coats. The room is simple and functional, each bed separated by a nylon curtain. The head of the bed can be raised mechanically and every component can be wiped clean. There are several fans and two air conditioning units that provide welcome relief from the heat outside. We start the round immediately at bed one.

Bed one: an 18-year-old G3P0 with eclampsia. She was seizing at home for about nine hours before she was brought in and delivered a deceased term baby last night. BP 185/101. No hyperreflexia, no headache. Magnesium treatment is halfway complete and she’s on labetalol. The labetalol is increased. Bed two: a 20-year-old G4P1, eclampsia. Seized again last night despite magnesium. There’s a low-grade fever and she’s drowsy and incoherent. We start a discussion: is it a postictal state, a stroke in progress, magnesium or the benzodiazepines used to break the seizure? Blood pressure is controlled, pupils equal and reactive, limbs are symmetrically hypotonic. Continue magnesium, check mag levels and electrolytes, rapid malaria screen. In my head I imagine the work-up she would receive in New York: a CT head, cultures from every orifice, anesthesia team on standby to intubate. Bed three: 25-year-old G6P3, eclampsia. She has finished magnesium treatment and is on oral antihypertensives.

Northern Nigeria has one of the highest rates of preeclampsia in the world. No one knows exactly why. It could be nutritional deficiency in magnesium or a genetic predisposition, but more universal reasons, such as second marriages with multiple gestations, cannot be ruled out. The American obstetrician on our team shakes his head. He’s never seen three recently eclamptic women in the same room before. “Sahnu?” The patient in bed three nods. “Sahnu” is Hausa, the predominant language in this area. It is one of those indispensable, Swiss Army pocketknife words: how are you?/I’m fine/hello/thank you/OK/I’m sorry. By the end of my mission it forms the backbone of my vocabulary.

We move on. Bed four: a 17-year-old G1P1, jaundice, abdominal distension, renal failure, lethargy, normotensive, no seizures. Her baby is in a crib beside the bed. We stand around scratching our medical heads. One of the local doctors suggests herbal toxicity. The woman has been taking a local herbal concoction of potash and plants to speed labor — her tongue is still dark from the ash. These mixtures are usually made by traditional healers and come with a high risk of liver failure. Will the lab do liver enzymes? Our new French lab technician has recently catalogued the reagents — she is hopeful. The obstetric ultrasound confirms ascites. I move up onto her chest. The curvilinear ultrasound probe just about fits between her ribs and I see a hyperdynamic, empty heart. We start IV fluids and discuss transfer to a larger state hospital.

The women in beds five and six have recovered from postpartum bleeds and are ready to move to the step-down beds in the adjacent room. Helene calls their names out the window. The central courtyard is full of waiting aunts and grandmothers who feed, wash and transfer our patients. “Fatima … Family of Fatima! Come to the ICU.” A few minutes later, Family of Fatima is cloaking her in a long hijab and bright cloth “wrappa,” the traditional dress in this area. They scoop up her brightly bundled baby and walk across the doorway into the general ward. Here she will have her own bed for a couple of nights, then she will share her bed with another postpartum patient before returning to her own village. As they pass me, the women raise their hands and bow their heads: “Sahnu! Sahnu! Sahnu!”

Bed seven: a 16-year-old G1P1 with anemia. Her presenting hemoglobin was 2, presenting complaint: dizziness while walking. She had delivered at home two days previously and her baby is beside her. After 4 units, the hemoglobin on our bedside fingerstick is now 6. She feels good. We debate transfusing another unit. She is nutritionally deprived and is about to spend the next few months breastfeeding. I grab the obstetric ultrasound probe (my echo). Her left ventricle is hyperdynamic and relatively empty. We take a vote and the transfusers win. We also add some high-calorie nutritional supplements.

We turn to our last bed. She’s 35, G5P2 with weakness. She was brought in by her family an hour ago, unresponsive. The story is that she delivered at home overnight. She then became confused and lost consciousness in the early hours of the morning. It’s now evening. The outgoing medical anesthetist educates me: only the men drive and they may be reluctant to travel at night or in poor weather. Our admissions come in mainly between 9 a.m. and 11 a.m., regardless of the onset of symptoms. Some women travel for days, from neighboring countries, for the free, highquality care that MSF delivers. The lucky ones come by car, the rest by oxcart. Our patient flails her left side but her right side is immobile. Blood pressure is uncontrolled, Babinski’s ... I have not checked for this sign since I was a medical student. I doubt myself and repeat the test. Up-going. Her prognosis is grim. Long-term treatment facilities and rehab units do not exist in Jahun and her ongoing care will place an enormous burden on her extended family. The team is silent for a moment, deeply aware of the repercussions if no recovery is made.

The static of a walkie-talkie breaks my reverie. India Charlie, this is Oscar Tango, do you copy? We copy. India Charlie, is the med anesthetist with you? We need help in Oscar Tango. Good copy, she’s coming.

Operating Theatre: Oscar Tango

The nurse anesthetist is struggling with an intubation. I take over and, after the tube is in, find out what is going on. Uterine rupture from a combination of eclampsia and protracted labor. Extra IV lines are secured and we cover her with a washable forced air warmer. Fresh blood is ordered from the blood bank. It arrives four minutes later, still warm from donation. In Jahun, the family of the patient “repays” by donating the number of units used by the patient. There is always a line of willing husbands and fathers on the bench outside the blood bank, waiting for a spot in the “bleeding room.” The type and screen is done on a large porcelain tablet. Blood is screened for hepatitis, HIV, syphilis and malaria. Malaria positive blood is still used — in an endemic area, too many units would be wasted otherwise — but the recipient is simultaneously treated. Packed cells are available for the neonates, everyone else gets whole blood.

Hysterectomy underway, I explore the drug cabinet. It’s fully stocked with a familiar family of emergency medications. Stacks of single-use syringes and needles are neatly organized. A separate, locked shelf contains controlled substances and there is a log book in the office nearby for periodic inspections by the Ministry of Health (MOH). All controlled substance containers are discarded separately. The MOH inspector will compare the log book with the collection of vials. While I understand how narcotics and benzodiazepines made the controlled list, the reason for locking up ephedrine, caffeine and methylergometrine is more of a mystery.

I turn to the anesthesia machine. I had read the orientation pack but the chrome box is quite different in practice. The nurse smiles. “Not like the one you are used to?” It reminds me of a gramophone from 1950.

I follow a standard mental algorithm: first find the “on” switch. There are six dials and two pressure gauges on the Monnal D2. My predecessor points out the pressure dial, rate setting and pressure alarms. There’s an oxygen blender and an isoflurane vaporizer. Monnal has continued manufacture of these simple models as a service to medical NGOs — they are easy to maintain, easy to transport and difficult to break. In terms of the circuit, everything except the endotracheal tube is reusable. The sterilization room has a counter window into the operating theatre — central supply gives us immediate service!

The next five weeks of my assignment pass quickly. I’m on call around the clock and every few days there is a soft nighttime knock at my door. Sometimes I’m called to help with mystery diagnoses (a thyroid storm, an acute non-obstetric abdomen, liver failure, psychosis mimicking a stroke) or to the operating room when a spinal won’t go in easily for an overnight C-section. I use the OB ultrasound for echo often, and rapidly discover that these young women have far from young hearts. Admissions for heart failure come in two or three times a week and some have concomitant valvular disease. I dredge up knowledge from medical school, consult my pocket pharmacopeia, and ask the local doctors if this is what a malaria spleen feels like. Every day I feel humble and grateful.

How to treat burnout? Talk to colleagues, get a massage? Rest on holiday? Quit your job? Become an administrator? Perhaps. For anyone who still has the embers of medicine alight, my advice is to drop the pressures of the Joint Commission, escape the clipboards and walk away from the man who didn’t like the “feel of the pillow” in PACU. Go and treat people who ask for nothing and give only gratitude in return. I hope I helped them. There is no doubt that they helped me. ■

Kiri Mackersey, M.D., is an attending cardiothoracic anesthesiologist at Montefiore Medical Center.

This article was printed in the NYSSA's Sphere Quarterly Publication - Volume 69 Number 2, Summer 2017

After the Earthquake: A Medical Volunteer’s Week in Haiti

This article was printed in the NYSSA's Sphere Quarterly Publication - Volume 65 Number 3, Fall 2013

by TIM MCCALL, M.D. & CINDY STRODEL MCCALL

Like many NYSSA members, I had the opportunity to volunteer in the aftermath of the devastating January 2010 earthquake in Haiti. I arrived on January 29, 2010, just as those involved in relief efforts had begun a series of helicopter airlifts to bring the severely injured from the earthquake zone to Sacré Coeur, which had organized surgical, medical and nursing teams to treat these patients.

The following account was written by my wife, Cindy, from daily texts and phone calls from me during my week working with a surgical team at Hôpital Sacré Coeur in Milot, northern Haiti. For the past three years I’ve returned to Milot with a surgical team from Central New York under the auspices of the CRUDEM Foundation, which oversees healthcare delivery at Hôpital Sacré Coeur. More information can be found at crudem.org.

Our team flew to Cap Haitian early in the morning. Roughly 90 miles from Port-au-Prince, Cap Haitian is a town of 100,000 that is now doubled in size due to refugees arriving from the earthquake zone. From Cap Haitian, the road to Milot where the hospital is located was like a three-ring circus, filled with vehicles and stalled traffic. Dirt roads were full of potholes and crowds of people walked in the middle of the road carrying loads on their heads. Huge UN trucks inched along in traffic along with rickety cars, vans and buses.

Milot is a pretty town of winding streets surrounded by forested mountains. The villagers in Milot are devoted to the hospital, Sacré Coeur, which has 73 beds and is now accommodating close to 400 patients. Since the quake decimated Port-au-Prince hospitals, UN inspectors consider Sacré Coeur the most modern and best equipped hospital in Haiti, and the only one currently capable of handling complex surgical cases.

Our team started working as soon as we arrived at Sacré Coeur. During our hospital tour, when we approached the OR area, we were asked, “Can you do a case now?” The ORs were mainly being used for wound debridement and amputations.

The hospital has three operating rooms and three procedure rooms that serve as makeshift ORs. A small, poorly equipped ICU is adjacent to the operating rooms. Operating rooms are dirty, with flies and mosquitoes everywhere. There is only one sink in the OR and intensive care areas for surgeons to scrub before cases, and for everyone else to wash their hands. One filthy, barely functional bathroom serves the area, with a toilet that doesn’t flush well.

At first it seemed there were no medical supplies. Later we realized the hospital has lots of supplies but they are so unorganized it’s difficult to find anything. Morphine is sitting in open bins everywhere. OR equipment and surgical supplies are all over the place in boxes on the cement floor.

With severely injured patients arriving continually by helicopter from Port-au-Prince, the situation seems like a war zone. The helicopters are also transferring patients from the USNS Comfort, a 1,000-bed naval hospital offshore of Port-au-Prince that has no more room for earthquake victims. The choppers land in a soccer field near the hospital compound. The wounded are brought out on stretchers and carried to Sacré Coeur’s makeshift ER, where they lie on the floor until hospital staff can get to them. Most patients wear triage pictograph tags on elastic cords around their necks. Sometimes the name of a patient is listed, sometimes not. One pictograph is a cross, which means nothing can be done — the patient is going to die. Another is a rabbit, which means get to the patient immediately. The third, a turtle, means the patient is not at immediate risk of dying. The patients are very stoic and wait patiently, even when in great pain, for medical staff to help them. The scope and the gravity of the physical injuries suffered by the injured, an overwhelming number of whom have not only lost limbs but are paralyzed or maimed, is staggering.

Sunday, January 31, 2010

Early this morning the hospital staff attended mass at Milot’s historic cathedral, Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception, built at the foot of the mountains. Full of families and small children dressed angelically in white, the huge basilica was packed. Its domed roof had a gaping hole through which the sky could be seen. During the Creole mass, the priest addressed the English-speaking medical volunteers and thanked them personally for their help during a time of crisis. At the end of the service, we found ourselves shaking hands with dozens of people who thanked us in Creole for our help.

Back at the hospital, the choppers started arriving. When helicopters fly in, the pilots

can’t radio ahead because of the mountain that hangs over the town. When the staff hears the choppers coming, everybody runs. There were 17 new surgical admits today by 2 p.m., many of them children. Orphaned kids arrived with adults they don’t know who brought them to the hospital, kids with traumatic amputations and broken bones who are so little they can barely tell you their names — 3-year-olds,

4-year-olds. The surgical team worked a 12- to 14-hour day in the OR.

Housing and feeding medical volunteers is a challenge for CRUDEM, the nonprofit that runs Sacré Coeur. The medical compound can accommodate about 12 volunteers at a time. Over the course of one week, the number went from 50 to 90. Some are housed in mosquito-proof tents equipped with cots, others in cement block rooms sleeping under mosquito netting on mattresses on the floor, eight people side by side. Some volunteers will be at Sacré Coeur for a week. Others come for a month. The medical compound must accommodate them all.

Hospital resources are even more stretched. Across the street is a school compound turned hospital ward where the injured lie on concrete floors with a mat underneath them. A mobile 200-bed hospital is arriving soon, donated through Caritas of Boston.

Our team is feeling the shock of being in the middle of such an enormous medical catastrophe. Late in the afternoon, a 4-year-old boy in a diabetic coma was brought in and died shortly afterward of cardiac arrest. At this evening’s staff meeting, tears, second-guessing and guilt gave way to an understanding that all present did their best to save the boy. We realized we needed to trust in ourselves, do our best under the working conditions, and learn how to make do with what is at hand in the OR.

Monday, February 1, 2010

The mobile hospital has arrived and is ready for patients. Red Cross workers and Haitian teenagers from the Boy Scouts work with the nuns and hospital staff to move the injured. The Caritas tents cost thousands of dollars to transport and set up. Similar hospitals have been used in places like Iraq and Afghanistan. The hospital consists of five large tents parallel to each other, each about 40 yards long, with 200+ cots supplied for patients. It’s a big improvement for patients who have been lying on the floor.

Most of the injured have infected amputations and badly healed wounds, lots of burns with skin grafts needed, and/or broken bones that aren’t set right. Infections and bedsores are very common. By afternoon, about 10 helicopters have landed, full of earthquake victims. The choppers are Army, Navy, Coast Guard, UN, French and other military helicopters. Patients come in on stretchers, as there are no carts or wheeled gurneys. The injured are lifted from the ground and carried around the hospital and wards by medical staff and aid workers.

There are no gowns for patients. Some have family members who bring them clothes. Most don’t. Many of the injured arrive with just the clothes on their backs. One patient who had been given a set of scrub pants to wear, a young man in his 20s, had a badly fractured ankle. He was in a lot of pain after surgery, but he was more anxious about losing his jeans because he knew they wouldn’t fit over the cast. Like most Haitians, the patient spoke only Creole. When the volunteers finally understood the situation, the jeans were rolled up and set carefully next to him under his shirt. Two Haitian-American medical volunteers who work side by side with the doctors speak fluent Creole and are indispensable to the team.

The medical team is seeing some of the most complicated cases we’ve ever encountered. There is little or no lab work, and most patients are anemic and malnourished. There is very little blood available. Patients do not have adequate nursing care, and the hospital doesn’t provide food for them. If they have family, the family bathes and feeds them, changes dressings, turns them over. For those without family, sometimes they find angels in fellow patients who have less serious injuries. Many patients are being fed by the villagers who walk up every day with food cooked at home. The villagers also provide care as best they can to patients without families, and try to take in those discharged from Sacré Coeur who are ill and alone. Patients are reluctant to be discharged as they have nowhere to go, and know no one in the area. Many are not well enough to get home, if they still have a home.

By day’s end the team members were feeling disheartened and overwhelmed. However, we could see that even in the face of such a catastrophic disaster, the Haitian hospital staff continued to do their best, no matter what came their way. We need to learn to take care of what is in front of us and keep going.

Tuesday, February 2, 2010

The team has had time to organize ORs and the wards, and sort medical supplies and medicines. Medical staff meetings are held every night at 8:30 p.m. — the surgery team can’t always make them as we often operate until 9:00 p.m. — and the hospital staff is making great progress at cutting down the chaos and getting things under control. An air-conditioned storeroom is overflowing but that’s a good thing. More medical supplies and medicines come in every day.

The work of carrying patients and equipment into the tents is under way. Most patients are now in cots in the mobile hospital, although it’s not quite up and running. The floor is coming on Saturday. Right now plastic tarps are laid on the ground. The tents are powered by a super loud generator that makes it hard to hear anything, but at least there’s power. One tent is for men and another for women. This makes sense, as there is no privacy and there are no bathroom facilities. Patients use bed pans, the contents of which are thrown into 10-gallon buckets that are carried outside and disposed of somehow.

UN and UNESCO personnel, Air Force and Army soldiers have been around all day, helping the medical staff set up the mobile hospital. There are still hundreds of boxes everywhere.

Today there were 30 cases in the three ORs and three procedure rooms. Two of the ORs are air-conditioned. The three additional procedure rooms where surgery is done are makeshift spaces but they work. The team administers pain meds and changes dressings in there whenever possible. It’s very painful for patients to have dressings changed on the wards, especially with burns. Without enough nursing staff to care for patients, bedsores and infections are a serious problem.

The team is still doing mostly amputations and cleaning out infected injuries, or fractures that haven’t healed well. Many children and teenagers who arrive by helicopter require amputations. They are reluctant to have surgery and don’t want anesthesia to be administered, terrified that they will wake up without a limb.

Wednesday, February 3, 2010

A 2-month-old baby girl who arrived yesterday, discovered under the rubble beneath six dead adults a week after the earthquake, is doing fine today. She has a crush wound on one buttock. Her mother is with her, which is good to see as there are so many orphans.

Another newly arrived patient, 30-year-old Nathalie, has a smile that lights up the room. Nathalie helps others as much she can although she has a left leg AKA and a right arm amputated above the elbow. She speaks some English, and from her wheelchair she helps direct the staff to those who are in serious pain.

One of the mobile tents has become the ER where new patients are stabilized. The four-man Haitian transport team that delivers patients to the OR is extremely hard working and keeps the ORs functioning efficiently. Helicopters come in daily with more wounded but patients are not as injured or critically ill. The triage pictographs are gone. Patients come in from field hospitals in Port-au-Prince with signs taped to them indicating their injuries. There are lots of new patients every day but less trauma and less critical injury.

Many people are paralyzed due to injuries from the quake. We see young paralyzed patients with extensive, severe bedsores that will end up causing fatal infections — a terrible heartbreaker. Inadequate nursing care causes serious problems on the wards. Essential medications are not being given. Too many patients aren’t getting antibiotics regularly, or at all.

More tents have gone up as new medical volunteers, mostly Americans or Canadians, have arrived. The tents are located near the field where the helicopter lands. Among the volunteers are military docs, top-notch surgeons with experience working in combat zones in Iraq and Afghanistan. A rooster has begun to patrol the tent area and begins crowing at midnight. After the first night, the team doesn’t even hear him.

Thursday, February 4, 2010

There were 24 OR cases today — a long day.

The hospital staff has better organized the meds. Now it’s written on a patient’s dressing when it should be changed next, and when the next dose of antibiotics should be administered. Medications are taped to a patent’s dressing as well. Pain meds are critical. In the halls, patients are moaning in pain. The best you can do is give out morphine on the spot. No sign-outs or protocol with morphine or other pain meds — the anesthesiologists all keep morphine with them, and administer it right away to those who need it. Many patients are in terrible pain.

A crowd of people waits outside the hospital compound, as a new policy is in place that only two people may stay in the wards with a family member. Hundreds congregate at the hospital gates, hanging out all day. The team hears rumors that troublemakers are here, that Port-au-Prince jails collapsed and let out all the criminals. An armored UN vehicle is parked in front of the hospital every night.

The team walked into town in the evening. Motorbikes roared past. Small children waved from doorways. Goats grazed in sparse patches of grass between cement block houses. Through a cemetery gate we saw bones on the grass. Haitians pay a fee to keep their dead in the ground. If they can’t continue to pay, the bones are dug up and scattered. People walked by with loads on their heads: huge bundles of sticks, plastic bottles filled with gasoline. Near the basilica the team crossed a bridge that spans a filthy river full of trash, pigs rooting in the water.

Stray dogs are all around. During the night a big gang of them had a fight by the volunteer tents. There is lots of action by the tents between the dogs and the rooster. Chickens are numerous around the compound, too, and some end up on our plates. The food is very good — rice and beans and different stews.

Friday, February 5, 2010

Things are slowing down in terms of surgery. The next step is to get more nurses, physical therapists and rehab volunteers. The tent hospital may only be needed for a month or so, as people recover and are discharged. It’s unclear where they will go, as so many of their homes were destroyed. Medical issues are compounded by social and political problems. For example, a young boy from the earthquake zone was diagnosed with leukemia early in the week. Attempts made to transfer him out of the country for chemotherapy in an American hospital were unsuccessful, as the hospital was unable to locate the boy’s family to get permission for him to leave.

There are so many problems and there is so much sadness. The medical volunteers talk to patients every day who tell them about the family members they lost in the earthquake. They point to the sky and say their lost family is in heaven — ciel in French. There are so many orphans, more every day. It breaks your heart.

I am leaving tomorrow but feel as if a part of me will stay here. How can anyone leave in the middle of such need and suffering? It will take time to process all that has happened. It will be hard to say goodbye.

This article was printed in the NYSSA's Sphere Quarterly Publication - Volume 65 Number 3, Fall 2013

Like many NYSSA members, I had the opportunity to volunteer in the aftermath of the devastating January 2010 earthquake in Haiti. I arrived on January 29, 2010, just as those involved in relief efforts had begun a series of helicopter airlifts to bring the severely injured from the earthquake zone to Sacré Coeur, which had organized surgical, medical and nursing teams to treat these patients.

The following account was written by my wife, Cindy, from daily texts and phone calls from me during my week working with a surgical team at Hôpital Sacré Coeur in Milot, northern Haiti. For the past three years I’ve returned to Milot with a surgical team from Central New York under the auspices of the CRUDEM Foundation, which oversees healthcare delivery at Hôpital Sacré Coeur. More information can be found at crudem.org.

- Tim McCall, M.D.

Our team flew to Cap Haitian early in the morning. Roughly 90 miles from Port-au-Prince, Cap Haitian is a town of 100,000 that is now doubled in size due to refugees arriving from the earthquake zone. From Cap Haitian, the road to Milot where the hospital is located was like a three-ring circus, filled with vehicles and stalled traffic. Dirt roads were full of potholes and crowds of people walked in the middle of the road carrying loads on their heads. Huge UN trucks inched along in traffic along with rickety cars, vans and buses.

Milot is a pretty town of winding streets surrounded by forested mountains. The villagers in Milot are devoted to the hospital, Sacré Coeur, which has 73 beds and is now accommodating close to 400 patients. Since the quake decimated Port-au-Prince hospitals, UN inspectors consider Sacré Coeur the most modern and best equipped hospital in Haiti, and the only one currently capable of handling complex surgical cases.

Our team started working as soon as we arrived at Sacré Coeur. During our hospital tour, when we approached the OR area, we were asked, “Can you do a case now?” The ORs were mainly being used for wound debridement and amputations.

The hospital has three operating rooms and three procedure rooms that serve as makeshift ORs. A small, poorly equipped ICU is adjacent to the operating rooms. Operating rooms are dirty, with flies and mosquitoes everywhere. There is only one sink in the OR and intensive care areas for surgeons to scrub before cases, and for everyone else to wash their hands. One filthy, barely functional bathroom serves the area, with a toilet that doesn’t flush well.

At first it seemed there were no medical supplies. Later we realized the hospital has lots of supplies but they are so unorganized it’s difficult to find anything. Morphine is sitting in open bins everywhere. OR equipment and surgical supplies are all over the place in boxes on the cement floor.

With severely injured patients arriving continually by helicopter from Port-au-Prince, the situation seems like a war zone. The helicopters are also transferring patients from the USNS Comfort, a 1,000-bed naval hospital offshore of Port-au-Prince that has no more room for earthquake victims. The choppers land in a soccer field near the hospital compound. The wounded are brought out on stretchers and carried to Sacré Coeur’s makeshift ER, where they lie on the floor until hospital staff can get to them. Most patients wear triage pictograph tags on elastic cords around their necks. Sometimes the name of a patient is listed, sometimes not. One pictograph is a cross, which means nothing can be done — the patient is going to die. Another is a rabbit, which means get to the patient immediately. The third, a turtle, means the patient is not at immediate risk of dying. The patients are very stoic and wait patiently, even when in great pain, for medical staff to help them. The scope and the gravity of the physical injuries suffered by the injured, an overwhelming number of whom have not only lost limbs but are paralyzed or maimed, is staggering.

Sunday, January 31, 2010

Early this morning the hospital staff attended mass at Milot’s historic cathedral, Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception, built at the foot of the mountains. Full of families and small children dressed angelically in white, the huge basilica was packed. Its domed roof had a gaping hole through which the sky could be seen. During the Creole mass, the priest addressed the English-speaking medical volunteers and thanked them personally for their help during a time of crisis. At the end of the service, we found ourselves shaking hands with dozens of people who thanked us in Creole for our help.

Back at the hospital, the choppers started arriving. When helicopters fly in, the pilots

can’t radio ahead because of the mountain that hangs over the town. When the staff hears the choppers coming, everybody runs. There were 17 new surgical admits today by 2 p.m., many of them children. Orphaned kids arrived with adults they don’t know who brought them to the hospital, kids with traumatic amputations and broken bones who are so little they can barely tell you their names — 3-year-olds,

4-year-olds. The surgical team worked a 12- to 14-hour day in the OR.

Housing and feeding medical volunteers is a challenge for CRUDEM, the nonprofit that runs Sacré Coeur. The medical compound can accommodate about 12 volunteers at a time. Over the course of one week, the number went from 50 to 90. Some are housed in mosquito-proof tents equipped with cots, others in cement block rooms sleeping under mosquito netting on mattresses on the floor, eight people side by side. Some volunteers will be at Sacré Coeur for a week. Others come for a month. The medical compound must accommodate them all.

Hospital resources are even more stretched. Across the street is a school compound turned hospital ward where the injured lie on concrete floors with a mat underneath them. A mobile 200-bed hospital is arriving soon, donated through Caritas of Boston.

Our team is feeling the shock of being in the middle of such an enormous medical catastrophe. Late in the afternoon, a 4-year-old boy in a diabetic coma was brought in and died shortly afterward of cardiac arrest. At this evening’s staff meeting, tears, second-guessing and guilt gave way to an understanding that all present did their best to save the boy. We realized we needed to trust in ourselves, do our best under the working conditions, and learn how to make do with what is at hand in the OR.

Monday, February 1, 2010

The mobile hospital has arrived and is ready for patients. Red Cross workers and Haitian teenagers from the Boy Scouts work with the nuns and hospital staff to move the injured. The Caritas tents cost thousands of dollars to transport and set up. Similar hospitals have been used in places like Iraq and Afghanistan. The hospital consists of five large tents parallel to each other, each about 40 yards long, with 200+ cots supplied for patients. It’s a big improvement for patients who have been lying on the floor.

Most of the injured have infected amputations and badly healed wounds, lots of burns with skin grafts needed, and/or broken bones that aren’t set right. Infections and bedsores are very common. By afternoon, about 10 helicopters have landed, full of earthquake victims. The choppers are Army, Navy, Coast Guard, UN, French and other military helicopters. Patients come in on stretchers, as there are no carts or wheeled gurneys. The injured are lifted from the ground and carried around the hospital and wards by medical staff and aid workers.

There are no gowns for patients. Some have family members who bring them clothes. Most don’t. Many of the injured arrive with just the clothes on their backs. One patient who had been given a set of scrub pants to wear, a young man in his 20s, had a badly fractured ankle. He was in a lot of pain after surgery, but he was more anxious about losing his jeans because he knew they wouldn’t fit over the cast. Like most Haitians, the patient spoke only Creole. When the volunteers finally understood the situation, the jeans were rolled up and set carefully next to him under his shirt. Two Haitian-American medical volunteers who work side by side with the doctors speak fluent Creole and are indispensable to the team.

The medical team is seeing some of the most complicated cases we’ve ever encountered. There is little or no lab work, and most patients are anemic and malnourished. There is very little blood available. Patients do not have adequate nursing care, and the hospital doesn’t provide food for them. If they have family, the family bathes and feeds them, changes dressings, turns them over. For those without family, sometimes they find angels in fellow patients who have less serious injuries. Many patients are being fed by the villagers who walk up every day with food cooked at home. The villagers also provide care as best they can to patients without families, and try to take in those discharged from Sacré Coeur who are ill and alone. Patients are reluctant to be discharged as they have nowhere to go, and know no one in the area. Many are not well enough to get home, if they still have a home.

By day’s end the team members were feeling disheartened and overwhelmed. However, we could see that even in the face of such a catastrophic disaster, the Haitian hospital staff continued to do their best, no matter what came their way. We need to learn to take care of what is in front of us and keep going.

Tuesday, February 2, 2010

The team has had time to organize ORs and the wards, and sort medical supplies and medicines. Medical staff meetings are held every night at 8:30 p.m. — the surgery team can’t always make them as we often operate until 9:00 p.m. — and the hospital staff is making great progress at cutting down the chaos and getting things under control. An air-conditioned storeroom is overflowing but that’s a good thing. More medical supplies and medicines come in every day.

The work of carrying patients and equipment into the tents is under way. Most patients are now in cots in the mobile hospital, although it’s not quite up and running. The floor is coming on Saturday. Right now plastic tarps are laid on the ground. The tents are powered by a super loud generator that makes it hard to hear anything, but at least there’s power. One tent is for men and another for women. This makes sense, as there is no privacy and there are no bathroom facilities. Patients use bed pans, the contents of which are thrown into 10-gallon buckets that are carried outside and disposed of somehow.

UN and UNESCO personnel, Air Force and Army soldiers have been around all day, helping the medical staff set up the mobile hospital. There are still hundreds of boxes everywhere.

Today there were 30 cases in the three ORs and three procedure rooms. Two of the ORs are air-conditioned. The three additional procedure rooms where surgery is done are makeshift spaces but they work. The team administers pain meds and changes dressings in there whenever possible. It’s very painful for patients to have dressings changed on the wards, especially with burns. Without enough nursing staff to care for patients, bedsores and infections are a serious problem.

The team is still doing mostly amputations and cleaning out infected injuries, or fractures that haven’t healed well. Many children and teenagers who arrive by helicopter require amputations. They are reluctant to have surgery and don’t want anesthesia to be administered, terrified that they will wake up without a limb.

Wednesday, February 3, 2010

A 2-month-old baby girl who arrived yesterday, discovered under the rubble beneath six dead adults a week after the earthquake, is doing fine today. She has a crush wound on one buttock. Her mother is with her, which is good to see as there are so many orphans.

Another newly arrived patient, 30-year-old Nathalie, has a smile that lights up the room. Nathalie helps others as much she can although she has a left leg AKA and a right arm amputated above the elbow. She speaks some English, and from her wheelchair she helps direct the staff to those who are in serious pain.

One of the mobile tents has become the ER where new patients are stabilized. The four-man Haitian transport team that delivers patients to the OR is extremely hard working and keeps the ORs functioning efficiently. Helicopters come in daily with more wounded but patients are not as injured or critically ill. The triage pictographs are gone. Patients come in from field hospitals in Port-au-Prince with signs taped to them indicating their injuries. There are lots of new patients every day but less trauma and less critical injury.

Many people are paralyzed due to injuries from the quake. We see young paralyzed patients with extensive, severe bedsores that will end up causing fatal infections — a terrible heartbreaker. Inadequate nursing care causes serious problems on the wards. Essential medications are not being given. Too many patients aren’t getting antibiotics regularly, or at all.

More tents have gone up as new medical volunteers, mostly Americans or Canadians, have arrived. The tents are located near the field where the helicopter lands. Among the volunteers are military docs, top-notch surgeons with experience working in combat zones in Iraq and Afghanistan. A rooster has begun to patrol the tent area and begins crowing at midnight. After the first night, the team doesn’t even hear him.

Thursday, February 4, 2010

There were 24 OR cases today — a long day.

The hospital staff has better organized the meds. Now it’s written on a patient’s dressing when it should be changed next, and when the next dose of antibiotics should be administered. Medications are taped to a patent’s dressing as well. Pain meds are critical. In the halls, patients are moaning in pain. The best you can do is give out morphine on the spot. No sign-outs or protocol with morphine or other pain meds — the anesthesiologists all keep morphine with them, and administer it right away to those who need it. Many patients are in terrible pain.

A crowd of people waits outside the hospital compound, as a new policy is in place that only two people may stay in the wards with a family member. Hundreds congregate at the hospital gates, hanging out all day. The team hears rumors that troublemakers are here, that Port-au-Prince jails collapsed and let out all the criminals. An armored UN vehicle is parked in front of the hospital every night.

The team walked into town in the evening. Motorbikes roared past. Small children waved from doorways. Goats grazed in sparse patches of grass between cement block houses. Through a cemetery gate we saw bones on the grass. Haitians pay a fee to keep their dead in the ground. If they can’t continue to pay, the bones are dug up and scattered. People walked by with loads on their heads: huge bundles of sticks, plastic bottles filled with gasoline. Near the basilica the team crossed a bridge that spans a filthy river full of trash, pigs rooting in the water.

Stray dogs are all around. During the night a big gang of them had a fight by the volunteer tents. There is lots of action by the tents between the dogs and the rooster. Chickens are numerous around the compound, too, and some end up on our plates. The food is very good — rice and beans and different stews.

Friday, February 5, 2010

Things are slowing down in terms of surgery. The next step is to get more nurses, physical therapists and rehab volunteers. The tent hospital may only be needed for a month or so, as people recover and are discharged. It’s unclear where they will go, as so many of their homes were destroyed. Medical issues are compounded by social and political problems. For example, a young boy from the earthquake zone was diagnosed with leukemia early in the week. Attempts made to transfer him out of the country for chemotherapy in an American hospital were unsuccessful, as the hospital was unable to locate the boy’s family to get permission for him to leave.

There are so many problems and there is so much sadness. The medical volunteers talk to patients every day who tell them about the family members they lost in the earthquake. They point to the sky and say their lost family is in heaven — ciel in French. There are so many orphans, more every day. It breaks your heart.

I am leaving tomorrow but feel as if a part of me will stay here. How can anyone leave in the middle of such need and suffering? It will take time to process all that has happened. It will be hard to say goodbye.

This article was printed in the NYSSA's Sphere Quarterly Publication - Volume 65 Number 3, Fall 2013